Ch. 1 Moops and Bones. Dad and Mom are in their 90s. They are still living in the apartment in Queens where I grew up, and which served as their art studio for most of their lives. And something drew me to understand Dad’s mysterious drawings, connecting them with stories from the past.

Ch. 2 Changes. As Dad and Mom have gotten older they began to have trouble living on their own. Things came to a head when Dad had to have a partial hip replacement and Mom could no longer care for him by herself. Mom suffered terribly living alone when Dad was in rehab, and I worked hard to arrange for home care even though Mom did not welcome it.

Ch. 3 I Am the Giver. Mom did not welcome the help because she had always been the giver. She had been hands on in caring for my brother and I when we were little. She did most of the cooking and cleaning. And she took care of Dad too, even while actively painting and publishing herself.

Ch. 4 The Hero of the Story. Dad agrees to collaborate on the graphic memoir project when I reassure him that he is the hero of the story. We look through some of his old sketchbooks together, and recall some of the drama of his young adulthood, before he became an artist. This project affords a welcome reprieve from my earlier focus on health and safety.

Ch. 5 Kluwital. This chapter explores my relationship with Dad growing up. He was already deeply immersed in his world of Moops, and sometimes didn’t have time for me. But I from an early age I admired his work. We page through his sketchbooks, we note the inspiration of Klee, Lewitt, et al (Kluwital), as well as Kuba textiles.

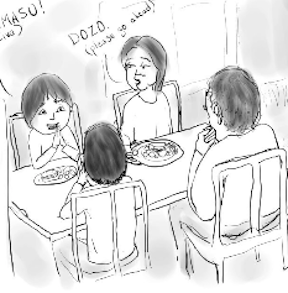

Ch. 6 Everyday Rituals. Through a number of everyday rituals—opening the mail, wordplay, and jokes at mealtime and potty time—Dad maintains a surprising levity despite the hardships of advanced age. I worry that that our graphic memoir project focusing on his artwork might actually bring back the painful desire for recognition when he finally seems free of care.

Ch. 7 Text and Image. Dad and I discuss the writing systems that he invented. I ask why invent writing systems that no one but he can read? He suggests that it served as a means of developing surprising visual compositions that had only incidental connection if any to the meaning of the phrases he encoded in them. We ponder the power of images, when we long for words, and when images serve us better.

Ch. 8 Documenting the Progress of My Decrepitude. Dad painted a self-portrait in his late 80s with a contorted expression that emphasized his age. He has made a ritual of having his grand-children all do portraits of him when they visit. These portraits document his gradual decrepitude, even as the kids’ draftsmanship improves.

Ch. 9 What Am I Doing Here? Dad’s dementia progresses, with episodes of confusion and anger that break the levity of his everyday rituals. I discover the wording he uses in one of his particularly striking compositions and I consider the connection between some of the trauma he experienced in his earlier life and his later artistic output. Dad resists a reductionist understanding.

Ch. 10 Epilogue. Dad painted a 50-meter mural in a corridor connecting the State Theater and Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center in New York City that stood from 1979 to 2008. We return to the question of text and image, and we explore another perspective on the source of Dad’s creative impulse.

I suppose we all want to be appreciated, and yet perhaps we prefer not to be completely transparent. Dad made himself visible, and yet in many ways opaque, hiding something in his images that suggested meaning but could not be completely deciphered. But language is a shared project. Dad’s art was an invitation for all to try to understand. This collaborative book project is the result of my accepting his invitation.